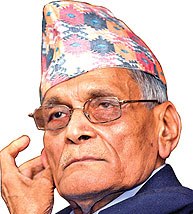

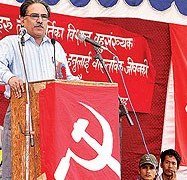

Considering the number of physical attacks his party has come under from the Seven Party Alliance (SPA) and the Maoists, you would think Rabindra Nath Sharma is the most reviled politician in Nepal. But the man is certainly on a roll.

Considering the number of physical attacks his party has come under from the Seven Party Alliance (SPA) and the Maoists, you would think Rabindra Nath Sharma is the most reviled politician in Nepal. But the man is certainly on a roll.With every assault, he sounds more persuasive as a committed constitutional (note not ceremonial) monarchist. Sharma probably expected the current spree of revulsion from the moment he took over the presidency of the Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP) faction that was part of King Gyanendra’s regime.

Pashupati Shamsher Rana, the head of the united RPP, refused to recognize King Gyanendra’s takeover. The SPA and Maoists refuse to recognize his RPP faction as anything but a palace appendage. Sharma, who unsuccessfully challenged Rana for the RPP presidency in late 2002, has taken a huge political risk by taking over as head of faction led by disgraced home minister Kamal Thapa. He seems to have drawn much of Thapa’s zeal to build the faction as the real RPP.

To understand Sharma’s persistence, you have to delve deeper into his politics. (Actually, those close to him say he beat great odds in a highly fractious extended family to survive childhood. But that is a different story.)

Rising up the Panchayat ranks, Sharma became quite candid about his prime ministerial ambitions. When King Birendra announced the referendum in May 1979, Sharma was among the few panchas that crossed over to the multiparty side. As campaigning progressed, Sharma braved a number of physical attacks.

He didn’t amount much in the anti-panchayat camp. He didn’t seem to ruffle feathers in the palace, either. Those who saw King Birendra attend Sharma’s daughter’s wedding easily put their money on the man.

He lost the first direct elections to the Rastriya Panchayat in 1981, but won a seat in the unicameral partyless legislature five years later. He was among the four serious prime ministerial candidates after the death of Lokendra Bahadur Chand’s father put the frontrunner out of the race. (The monarch could not swear in a man in his year of mourning, we were told then.)

Once Marich Man Singh had added Shrestha to his name, it was clear he was the palace top choice. Asked whether he would serve in a Shrestha cabinet, Sharma reminded many that the prime minister-designate had once served as his assistant minister. If that sounded like a resounding no, the pledge didn’t last long. About a year later, Sharma briefly joined Shrestha’s cabinet.

The collapse of the Panchayat system thrust Sharma into the wilderness. But not for too long. Many credit him with ensuring that the RPP was born as twins. From the convoluted electoral formula emanating from a hung parliament, Sharma won a seat in the upper house.

When Girija Prasad Koirala conned Sher Bahadur Deuba into taking that vote of confidence he was not constitutionally required to and then prevented two Nepali Congress MPs from casting their ballots, Sharma was quietly waiting in the wings.

Before Koirala could stake his claim to form the next government, Sharma had already struck an alliance with Bam Dev Gautam of the UML and intimated the palace.

He became finance minister in the cabinet nominally headed by Lokendra Bahadur Chand. Yet Sharma was the only RPP man who could stand up to Deputy Prime Minister Gautam. By now, he had earned the soubriquet of ‘Chanakya’ of Nepalese politics.

Acknowledging that he was not the first and would not be the last finance minister to preside over financial malfeasance, Sharma collectivized responsibility for corruption. In the RPP, he seemed to be allied with Surya Bahadur Thapa, who succeeded Chand as premier. Apparently, the wily man refused to anoint Sharma as his successor. (Maybe he never forgave Sharma for having catapulted Chand to the premiership first.) Rana beat Sharma as Nepal headed into uglier conflict.

When Thapa returned as the second premier King Gyanendra directly appointed, Sharma was overseas. He was persuaded to return to serve as a minister, some say by Thapa himself. When Sharma landed at Tribhuvan International Airport, he was detained on corruption allegations. Thapa probably wanted to prove that he wouldn’t spare his own, but it didn’t help him get Koirala’s support. In fact, the RPP couldn’t unite behind its former president, forcing Thapa to form his own Rastriya Janshakti Party.

Amid such complexities, it was hard to see Sharma heading a party of his own. Now that he has, the contours of realignment are becoming apparent. Although they differ on the exact adjective to precede the institution, Koirala, Thapa and Sharma are leading advocates of the monarchy. All three share close allies in New Delhi’s political establishment. The youngest of the three, Sharma’s ambitions must be the most zestful.