As headlines go, they were pithy. “Nepal to vote to trim king’s power.” “Nepal lawmakers demand that king relinquish control of army.” “New elected body to decide king's role.”

As headlines go, they were pithy. “Nepal to vote to trim king’s power.” “Nepal lawmakers demand that king relinquish control of army.” “New elected body to decide king's role.”Western news editors carried variations of the preceding three titles, carefully keeping the essence of the nut-graph: King Gyanendra is the principal obstacle to Nepal’s democracy and prosperity.

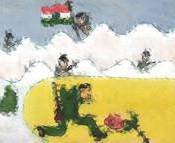

For a world attuned to color-coded revolutions in a minute-and-a-half segments, the televised images of Nepalese government forces killing and maiming street protesters proffered the solution. Chase or vote out the medieval monarch and Nepalis can reach for the moon.

The triumphant Seven-Party Alliance (SPA) leaders should have recognized the fallacy in that prescription. By zeroing in on the Constituent Assembly as a mechanism to oust the monarchy, the mainstream opposition may have appeased their egos bruised badly over four years of palace-driven marginalization. They shouldn’t be digging their own graves in such haste, at least not until the Maoists proved they were even remotely committed to multiparty democratic republicanism.

Although they have repeatedly vowed not to repeat the mistakes of their previous stint in power, SPA leaders have already done worse. Barely a year after promising how the restoration of multiparty democracy would turn Nepal into another Singapore, Nepali Congress and communists alike had to concede their lack of preparedness to govern. The tallness of their early promises played a major role in undercutting their credibility.

Let’s say everything works out according to plan this time. The Maoists and the SPA agree to conditions guaranteeing free and fair constituent assembly elections. Let’s say 90 percent of Nepalis vote in favor of abolishing the monarchy. (For the sake of the credibility of the exercise, the assumption here is that 10 percent of Nepalis are dim-witted and wrong-headed enough to want to keep the king. Hitler and Stalin, after all, still enjoy greater support.)

Under a republican constitution, the ex-Maoists fighters and ex-Royal Nepalese Army personnel are fused into a national army. Booting out the Ranas, Shahs, Thapas and Basnets won’t solve the problem. How are we going to reconcile the traditionally disadvantaged groups on the opposite armies raised on completely different standard operating procedures?

Even if they hit it off well personally, how can Bharat Bahadur Thapa Magar of the former Royal Nepal Army, trained in conventional combat, and Maoist fighter Ram Man Pun, with all his hit-and-run agility, be expected to get along professionally? How are their divergent attitudes, temperaments, motivations and training supposed to mesh into unity of purpose?

At the political level, the SPA and the Maoists may divvy up the presidency and premiership in the true tradition of the American spoils system. The Bahuns, Chettris and Newars that dominate each side will monopolize power and extend patronage. No matter how the military-mobilization modalities are worked out under the control of parliament, someone somewhere must have the ultimate authority to order the troops out of the barracks.

Despite all the calumnies heaped on them, the former RNA men (and women) – minus the Ranas, Shahs, Thapas and Basnets, of course – might still be driven by loyalty to the country. What about the former Maoist fighters driven by hatred for everything except their cause? Will they be able to dissociate themselves from the ideological inferno that got them this far?

This is just the monarchy-military dimension of the constituent assembly in the most optimistic scenario. We haven’t even addressed economic and social exclusion, lack of distributive justice, inequitable representation in state structures and regional disparities in development and all the other issues plaguing Nepal.

Vote out the monarchy in the constituent assembly and prosper? A nice slogan perhaps, but one that could boomerang with devastating effect quite fast. No wonder Prime Minister-designate Girija Prasad Koirala, rejecting an almost universal demand from his camp, went to Narayanhity Palace to be sworn in by King Gyanendra.

With Nepali Congress President Girija Prasad Koirala set to return as prime minister, a lot of Nepalis seem to be scratching their heads. After all that has happened over the past three tumultuous weeks, not too many people seem to have revised their view of the grand old man.

With Nepali Congress President Girija Prasad Koirala set to return as prime minister, a lot of Nepalis seem to be scratching their heads. After all that has happened over the past three tumultuous weeks, not too many people seem to have revised their view of the grand old man.