Nepal's Feb. 8 municipal elections have allowed all three of the kingdom's principal protagonists to emerge as victors. The Maoists could boast how successfully they sabotaged the latest plot of the tottering feudal order before withdrawing a general shutdown that was becoming increasingly unpopular among ordinary people.

Nepal's Feb. 8 municipal elections have allowed all three of the kingdom's principal protagonists to emerge as victors. The Maoists could boast how successfully they sabotaged the latest plot of the tottering feudal order before withdrawing a general shutdown that was becoming increasingly unpopular among ordinary people.The mainstream parties could claim that the Nepalese people responded overwhelmingly to their call to thwart King Gyanendra's effort to legitimize his takeover of full executive powers a year ago.

Over the preceding months, the seven-party anti-palace alliance could barely disguise its frustration at not being able to join the Maoists in violently resisting the polls without undermining their self-proclaimed commitment to democracy.

The royal government, for its part, proved that elections could be held in the worst of times. King Gyanendra clearly preferred to incur the wrath of democrats for holding elections, not for abandoning them.

Yeah, and turnout? Confronted with the fact that a quarter of 4,000 seats had no one standing at all, the palace probably had already figured out that the same rebel-induced fear would grip constituents.

For a regime facing scathing criticism at home and abroad for failing to keep its pledges, moreover, holding the local elections on schedule provided a rare opportunity to respond. After King Gyanendra, the man with the greatest stake in the polls was Home Minister Kamal Thapa. He must have uncorked a steady stream of champagne – figuratively, at least.

The United States was quick to denounce the polls as a sham. Much of the democratic world evidently shares the sentiment. Indeed, the legions withdrawing their nominations over the last two weeks citing threats from the Maoists were the respectable ones. Among them, one understands, were people who had personally assured the monarch of their participation, come what may.

Countless others pulled out saying they had no idea they had ever filed papers. There were no candidates or candidates stood unopposed in 22 municipalities. Of the contestants in the remaining 36 towns and cities, most were ordinary people. Of course, longtime advocates for ending the tight grip the elite have traditionally held on electoral politics kept quiet in view of their more immediate target: the palace.

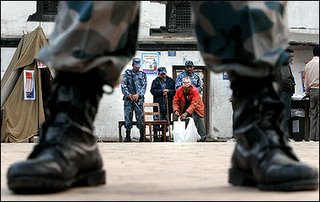

Candidates determined to stick until the end invariably fell under heavy military security. Anxious family members, more than armed rebels, seemed the real reason for the electoral hemorrhage. More bullets than ballots, the international media's favorite punch-line went.

In such circumstances, sham was hardly an inappropriate word. For many, the municipal polls have undoubtedly provided a glimpse of the shape of things to come in the national elections due next year.

In terms of immediate politics, the municipal polls have done little to shift the balance of power. For now, Nepalis would probably have to endure the stalemate that has wearied them for the last three years.

Not all may be doom and gloom, though. The 10 percent turnout, perhaps a fair estimate between the government's and opposition's propensity for exaggeration, is not that bad. That's about the same turnout in the Indian states of Punjab and Kashmir during the height of the insurgencies there.

Those elections are still cited as turning points in the Punjabis' and Kashmiris' road to recovery. Hoping against hope? One hopes not.