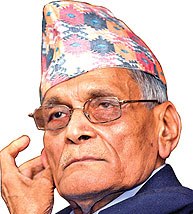

It seems Dr. Tulsi Giri has lost none of his caustic candor amid the debris of what he must have envisaged as a stunning political comeback. At informal political gatherings, we are told, the senior vice-chairman in the 15-month royal regime, mostly rants against King Gyanendra.

It seems Dr. Tulsi Giri has lost none of his caustic candor amid the debris of what he must have envisaged as a stunning political comeback. At informal political gatherings, we are told, the senior vice-chairman in the 15-month royal regime, mostly rants against King Gyanendra.For someone who once declared himself the mother of the Panchayat system, Dr. Giri is nothing if not a straight-shooter. A confidant of B.P. Koirala, he ditched Nepal’s first elected prime minister and joined hands with King Mahendra in a new political experiment. Unlike most panchas with backgrounds in political parties, Dr. Giri never made apologies for his conversion.

After India’s humiliating defeat in the 1962 war with China, Dr. Giri said Peking’s real aim was to get India off Nepal’s back. Whether Dr. Giri had any special insight into Chinese thinking is unclear. The fact that his quote still circulates in Indian media and academia underscores its psychological potency.

Dr. Giri’s disenchantment with the partyless system under King Birendra was real. He served as premier only to be shunted – and worse. He was tried for corruption in a carpet-export scandal along with some of his most energetic ministers. When King Birendra announced the referendum in 1979, the palace needed Dr. Giri’s oratory skills. He could oblige so easily because he saw the carpet scandal as a vast scheme of palace secretaries to emasculate the cabinet in a bid to concentrate power.

The victory of Panchayat system the following year brought little relief to its principal living architect. He saw an inherent contradiction between adult franchise and partylessness. Resigning as chairman of the committee organizing the silver jubilee of the Panchayat system, Dr. Giri left for exile in Sri Lanka and later India. This time the message to the palace was more meaningful.

Dr. Giri’s return from Bangalore to become the senior-most commoner wielding executive power in 2005 prompted some to wonder whether he could retain his pro-Nepal – his critics would say anti-India – posture. He was back in form. Hospitality foreigners accord a private citizen need not constrain his or her ability to perform public duties. (Where would we be today had Gandhi and Nehru remained eternally beholden to their lives as students in Britain?)

Rumblings of discontent emerged from Dr. Giri within months of his assuming power. Then, last month, he made the most crucial revelation: King Gyanendra’s Feb. 1, 2005 takeover occurred with India’s approval.

So why the Indian volte face? Because it is part of the Indian playbook. After foisting the 1950 Treaty on the tottering regime of Mohan Shamsher Rana in exchange for continued support, India crafted the Delhi Compromise. Now, Indians like to ascribe that policy “evolution” to the People’s Liberation Army’s invasion of Tibet after the signing of the 1950 treaty.

Yet the actual reason may be the inroads the isolationist Rana regime had been making in the Truman administration. With London and Washington on the verge of recognizing King Gyanendra I as the new monarch in November 1950, New Delhi used the tripartite consultations in many ways. Today Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala knows that the Nepali Congress erratic anti-Rana insurgency owed more to the unpredictability of India’s support than to any inconsistency in the insurgents’ zeal. Of course, he won’t say so.

Convinced he had kept the Americans and Brits out, Jawahar Lal Nehru didn’t lose a minute in ditching Mohan Shamsher. Of course, he emulated his Raj forbears in offering Mohan exile. (Kings Rana Bahadur Shah and Rajendra Bikram Shah spent time in Benaras.)

When King Mahendra dismissed B.P. Koirala’s government, deputy premier Subarna Shamsher Rana could evade arrest because he had left for Calcutta days earlier. It is said that the king had spoken of his intention during his trip to the west. As Subarna Shamsher was in the entourage, this departure was intriguing. Also noteworthy is that King Mahendra preferred Subarnaji as premier and had delayed inviting B.P. to form the government after the 1959 elections.

So the logical question is: Was Subarnaji supposed to have led the Nepali Congress faction backing the palace takeover? Was his departure to Calcutta to attend property matters merely a ploy to prevent that from happening? Was Subarna Shamsher’s 1968 statement of loyal cooperation with the palace a delayed version of the one he was to have returned to Kathmandu with six years earlier?

When Nepali Congress insurgents intensified their armed campaign after King Mahendra signed the agreement with the Chinese on building the Kodari Highway, New Delhi ruled out any link between the two developments. Here, too, Dr. Giri was at his brightest.

Asked by a Time magazine reporter to comment on Indian denials, Dr. Giri said: “The rebel leadership is in India. The money comes from India. The propaganda comes from India.” (“War in the Mountains”. March 9, 1962) A brilliant triple whammy.

For a government that could keep the letters exchange with the 1950 a secret for a decade, India sought mileage by “revealing” that King Mahendra somehow sold out Kalapani and compromised Nepalese sovereignty by signing the 1965 arms agreement. Twenty-two years later, few Nepalis recalled that Prime Minister Kirti Nidhi Bista’s eviction of the Indian military checkposts and mission included the repudiation of the 1965 accord.

Kalapani was very much on the royal agenda until King Mahendra’s death in 1972. No one in New Delhi will reveal what kind of implorations their government made to the palace to maintain their defensive posture after the Humiliation of Sixty-Two. Especially since India gets to denigrate King Mahendra’s nationalism as well as occupy the territory.

Against this sordid background, Dr. Giri’s latest disclosure warrant greater attention. Clearly, India used the first 10 months of the royal regime to bargain with the palace. It was only when King Gyanendra led the initiative to grant China observer status in South Asia’s premier organization that the Seven Party Alliance-Maoist combine gained traction in New Delhi. What kind of concessions was New Delhi trying to extract? A more stringent extradition treaty? Passage of the citizenship bill? Priority in the development of Nepal’s water resources? The oil concessions that helped catapult Cairn into the FT 100 index? Perhaps we can expect Dr. Giri to keep up his candor.