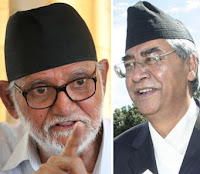

The Nepali Congress seems destined to live with the Koirala-Deuba hostilities. Party president Sushil Koirala has come to the point of publicly complaining that senior leader Sher Bahadur Deuba is not responding to his telephone calls. “Let us solve our differences through dialogue,” Koirala urged Deuba through the press the other day.

What began as a confrontation sparked by Koirala’s dissolution of four sister wings of the Nepali Congress – led by Deuba loyalists – remains rooted in the contrived reunification of the party in 2007 ahead of the constituency assembly elections.

While it has always made sense for Deuba to portray his dissidence as opposition to the arbitrariness of the leadership, the fact that the leader today happens to be surnamed Koirala helps him immensely. Nepali Congress members come from such diverse backgrounds that the party simply has too many fault-lines to cover. But who in the country’s largest democratic party could oppose a clarion call to free the organization from the clutches of a clan if it could cover the sundry motives they have?

Deuba himself has often conceded that, despite his bold public criticisms of Girija Prasad Koirala, he could not muster enough courage to put his grievances across directly to the grand old man. With Girijababu’s departure, Deuba no longer feels so constrained.

His crusade has changed in other ways. Prakash Man Singh, party general secretary and onetime loyalist, today warns Deuba of disciplinary action. (With Girijababu’s own departure from this mortal world, Prakash probably no longer sees the anti-Koirala campaign an extension of the travails of his late father, Ganesh Man Singh.)

Even among onetime loyalists in the Nepali Congress-friendly media, the mood has soured. Editors and columnists who once hailed his courage easily dismiss him today as a relic of the old Nepal.

None of this appears to have dissuaded Deuba. The other members of the Koirala clan are quiet. Sujata is laying low lest the controversy surrounding her son-in-law, Rubel, climb up the family ladder. As one of the original promoters of his party’s alliance with the Maoists, Shekhar is still crossing his fingers on where the 12-point experiment would lead.

The once-promising Shashank has been reduced to lamenting how Nepal has forgotten the national-reconciliation policy his father had propounded when there was actually a king to kick around.

Yet just as Deuba felt he had tamed the tribe, Sushil has shown a sudden itch to enter Baluwatar. The seeds of that ambition, sown during his visit to India earlier in the year, have been nurtured by the succeeding political shenanigans. If Girija Prasad Koirala could become prime minister without having ever served in a lower ministerial rung, what should stop Sushil?

As the notion of a national unity government animates the Nepali Congress, Deuba feels he is most qualified man to head it. You can’t blame him. The negatives associated with Deuba’s record have paled in comparison to what is going on today.

The Maoists have proved that the 40-point charter Deuba had rebuffed in 1996 was not the actual propellant of their decade-long insurgency. Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai has outdone Deuba in terms of bloating the cabinet. The ‘Pajero’ culture has turned viler both as a tool and outcome of political skulduggery.

Agreements far more toxic than the one on the Mahakali River have become commonplace. (At least during those days you could expect the principal opposition party to make a pretense of having split on account of anti-national agreements.)

As to the allegation that Deuba could not save democracy during his last two tenures as premier, isn’t it an article of faith among the current political class that true democracy ever existed in Nepal?

Looking ahead, maybe Deuba wants a new term to demonstrate that he is capable of something different, now that things have come full circle.