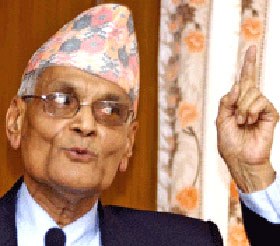

The royal regime seems to hold a huge grudge against Madhav Kumar Nepal. Nepalis were expecting to see the perennial premier in waiting freed from house arrest. Instead the mainstream’s comrade in chief has been whisked away to an undisclosed location by the Armed Police Force that was guarding him.

Home Minister Kamal Thapa won’t let us in on anything more than that you-can’t-misuse-communication-equipment-while-under-house-arrest bit. Was Makune exchanging seditious emails with his brothers? Why is the royal regime according Makune this, shall we say, special treatment?

Undoubtedly, the man has an extraordinary record of accomplishment. He emerges almost out of nowhere to help write the new democratic constitution in 1990. Then his boss, Madan Bhandari – who himself emerges from obscurity to lead the then Marxist-Leninists – offers only critical support to the statute.

A couple of years later, Madan Bhandari, along with an associate, dies in a mysterious car accident. Makune, an indirectly chosen member of the upper house of the legislature, is catapulted to the top. Few expect him to last long amid the bevy of more formidable comrades.

Makune and his allies spew fire on the streets about exposing the conspiracy behind Bhandari’s death. The protests help him consolidate his hold on the party. Once in government, as deputy premier of a minority government, Makune forgets all about the Dasdhunga accident.

Moreover, instead of revising the Tanakpur water resources accord with India, which Bhandari had led a crusade against, Makune ends up widening the net by agreeing to the Mahakali Package.

Makune’s boss, Prime Minister Manmohan Adhikari, confides in close associates that he feels freer discussing important matters with Nepali Congress leaders than with his own “boys.”

Adhikari dies while campaigning for the UML. Following the elections, the party finds itself on the opposition benches. Makune feels no need to fill the UML chairman’s post, arguing that Adhikari was a special case.

He spearheads the Lauda Air corruption scandal against Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala, until it emerges that the comrades are neck-deep in similar shady practices with China Southwest Airlines.

After the Narayanhity massacre, Makune advises King Gyanendra to form a high-power investigation committee to probe the tragedy. When the king does, he refuses to serve on the committee.

Having played his part in the ousting of Koirala, Makune not only hails Sher Bahadur Deuba’s rise; a few weeks later the UML takes out a procession in support of Deuba’s land-reform program.

He travels to Silguri for a secret meeting with Maoist supremo Prachanda, discovering that the leaders of almost all the mainstream communist factions have been invited. Prachanda later accuses him of divulging full details of those discussions to King Gyanendra. Makune responds by fully endorsing Deuba’s decision to mobilize the army against the rebels.

When time comes for extending the state of emergency, under which the army has been deployed, Makune wants concessions from Deuba. It’s couched in terms aimed at strengthening the supremacy of parliament over an assertive palace under King Gyanendra. Deuba feels the comrades want a permanent share in power through a national government.

Falling out with Koirala, following long-simmering rivalry, Deuba dissolves parliament. Koirala expels Deuba from the party. Makune welcomes the elections, saying the prime minister has full prerogative to call one.

Makune seeks to project an aura of political consistency, citing the UML’s opposition to the Supreme Court’s decision to restore the house dissolved by premier Adhikari in 1995. The real reason turns out to be his calculation that, in the midst of a divided Nepali Congress, the UML would win a majority.

When King Gyanendra fires Deuba on October 4, 2002 for his failure to hold the elections on time, the entire mainstream heaves a sigh of relief. Makune seemed the most enthused. Only when Lokendra Bahadur Chand becomes prime minister days later does the mainstream see a regressive palace.

The anti-palace campaign heats up. Makune promises to encircle Narayanhity with 100,000 people. Considering the UML’s organizational abilities, that was not a threat to be taken lightly. The U.S. State Department’s Christina Rocca lands in Kathmandu and meets Makune and other agitators. Suddenly the UML remembers the urgency of holding organizational elections in Janakpur.

Our wily Prachanda announces a ceasefire and begins peace talks with the palace-appointed government. Dr. Baburam Bhattarai is confident of leading a new coalition in power. If Krishna Prasad Bhattarai could do so in 1990, surely the Maoists have precedent on their side.

But Washington slaps the terrorist tag on the Maoists. The peace talks hit a roadblock. Chand’s days are numbered. Makune is the leading candidate to succeed him. Surya Bahadur Thapa, despite his troubled ties with Nirmal Niwas during the Panchayat years, freshly returned from a visit to India upstages Makune.

A war of words breaks out within the UML. Khadga Prasad Oli, who headed the dissidents at the Janakpur conference, is cozying up to the palace. Something big is about to happen in the UML.

Something does. Amar Lama, the driver of the land-cruiser in which Madan Bhandari and Jeev Raj Ashrit died, is about to make an explosive revelation. He is abducted and killed before he could get to the reporters.

The peace talks, which had been sputtering on, formally collapse. Surya Bahadur Thapa’s days seem numbered. But he seems to have some supernatural gift for survival.

Prachanda, meanwhile, is still on Makune’s mind. He heads to Lucknow for a meeting with the Maoists. Makune returns home saying Prachanda is willing to restart peace talks if they are held with an all-party government. A government informant is in the UML entourage. The only real news to emerge from the Lucknow talks: Dr. Baburam Bhattarai concedes that the Maoists can never come to power as long as they continue attacking India.

Dr. Bhattarai regains a fondness for his Jawahar Lal Nehru University days. Makune becomes our latter-day Dr. Keshar Jang Rayamajhi, the royal communist. Deuba already has been cast as Dr. Tulsi Giri. (Little did Nepalis know that the original men were not yet done on the political stage.)

Finally, months later, Surya Bahadur Thapa resigns. The mainstream alliance leaders can’t decide whether to meet King Gyanendra. When the leaders finally do, they cannot come up with a consensus candidate.

Makune reminds Koirala of the alliance’s earlier undertaking. The Nepali Congress chief says events have overtaken that commitment. Suspecting mischief, Makune decides to file a formal application with the palace secretariat. He goes to Koirala and the other leaders for their signature.

They smooth-talk him into filing the petition on his own behalf. Only later does Makune realize he has joined a long list of wackos and nut cases seeking the premiership. The country, meanwhile, is left without a government for almost a month.

An infuriated Makune ditches Koirala and Co. to back Deuba’s new coalition. With the reappointment of Deuba, he argues, the royal regression has been half corrected. He selects a safe contingent of ministers. The UML chief speaks from both sides of his mouth. His ministers are clueless about cabinet decisions.

The top palace nominee in the cabinet, Dr. Mohammed Mohsin, warns that the kingdom may soon enter a more authoritarian phase. Makune still can’t decide whether to remain in or leave the Deuba coalition.

King Gyanendra strikes on Feb.1, 2005. Makune is the last top leader to be freed from detention. He visits India like most of the other leaders. He sets himself apart, though, by using a forum there to blast the Chinese government for supporting the palace.

Back home he threatens to take members of the royal regime and the military to the International Criminal Court. He doesn’t bother to explain through which route because no one asks.

The political discourse becomes ambiguous. Loktantra replaces prajatantra as the Nepali equivalent of democracy. Then comes the term “total democracy.” Does this mean republicanism? Then the 12-point pact between the mainstream parties and the Maoists is unveiled.

Makune tries to take full credit for it. He argues that the accord was the outcome of a long process he had initiated with Prachanda in Silguri and Lucknow, among other places. Makune seemed to have rehabilitated himself among the Maoists. Could this singular record explain why the royal regime is singling him out?

The real obstacle to political reconciliation in Nepal is becoming ever more visible in the incessant whining that passes for news and analyses in the Indian media these days.

The real obstacle to political reconciliation in Nepal is becoming ever more visible in the incessant whining that passes for news and analyses in the Indian media these days.