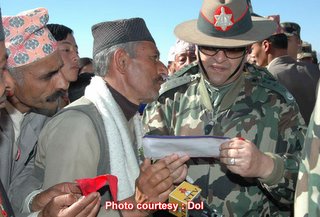

The Maoists end their four-month ceasefire and the Royal Nepalese Army halts its much-touted offensive in the rebel heartland of Rolpa. And the supreme commander in chief? He's busy trudging the rugged terrain of the rural east lending the people an ear.

The Maoists end their four-month ceasefire and the Royal Nepalese Army halts its much-touted offensive in the rebel heartland of Rolpa. And the supreme commander in chief? He's busy trudging the rugged terrain of the rural east lending the people an ear.What's going on in the royal mind?

Hard to know -- but certainly worth find out.

King Gyanendra's internal critics and international well-wishers miss a major point: his firm recognition that the Nepalese monarchy is facing a defining moment.

From the moment he ascended to the throne, King Gyanendra has been called all kinds of names – fratricide, murderer, plunderer. Autocrat is one of the pleasanter appellations.

Few people get to be king. Fewer still do so out of turn. How many have been crowned twice despite having been so far behind in the line of succession? If King Gyanendra seems impelled by destiny, he certainly has good reason. His critics' threats to turn Nepal into a republic aren't going to work.

The king abhors the notion of constitutional monarchy – at least the kind the Nepali Congress and the Unified Marxist-Leninists want. In his view, King Birendra was forced to remain a silent spectator not because the late monarch was afflicted by a sudden character or temperamental transformation.

There were many ways in which King Birendra could have tried to preserve his Panchayat-era powers. Whether he would have succeeded, we don't know. All we do know is that, after the power struggle over the new constitution, King Birendra withdrew.

Personally, for him, it was a brilliant move.

King Birendra succeeded in reinventing himself as constitutional monarch par excellence – to borrow the phrase of leading politicians in the opposition today -- as the icons of democratic struggle began falling off their pedestals.

After a point, though, personal fulfillment didn't seem to matter much. King Birendra shot off memos to elected governments on why the Maoist insurgency broke out after Nepal had become a fully functional democracy. He used the Supreme Court route to veto a controversial citizenship bill a unanimous legislature virtually imposed on him.

In the final weeks of his life, he set out to end that great southern discomfort. The Bharatiya Janata Party may have been a Hindu nationalist organization. But it was an Indian political organization first. Nepal-India relations reached their worst levels under the purveyors of Hindutva. The lessons were clear.

King Birendra saw Nepal's salvation in reaching out to the country's giant neighbor to the north. In other words, for much of the past year, King Gyanendra has merely picked up from where his late brother left off.

Next, it is important to consider the psychology at work here. We may make distinctions between democratically elected and blood-drenched premiers. It doesn't really matter to the monarch. The last time an all-powerful prime minister began eclipsing the palace in Nepal, the shadow lasted over a century.

Then there's pure human nature. If Girija Prasad Koirala and Madhav Kumar Nepal want life-long tenure as head of their parties, why should we expect the monarch to relinquish control of a country he feels his ancestor took the lead in building?

History has relevance, too. We can argue for ever on how much death, destruction and deceit defined the national unification campaign or whether Nepal today is really a unified nation-state.

King Gyanendra won't take those arguments seriously unless the proponents say they are willing to go back to the fractious days of the baisi-chaubise rajyas.

Well, why doesn't the monarch listen to the international community?

Because he's seen their hypocrisy upfront. For Jawahar Lal Nehru, Nepal's independence depended on who sat on the throne. King Gyanendra must have been too small to recall the pain of dethronement in 1951. The symbolism was no doubt searing, especially as it related to the policies of Nepal's southern neighbor.

Matters came full circle 50 years later. What did Indian diplomats K.V. Rajan and M.K. Rasgotra discuss with King Gyanendra on the morning of Oct 4, 2002, before he dismissed Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba's government?

Washington and London, too, left their imprint on that tender mind. After pledging to support the Rana regime's reincarnation into a political organization, the Gorkha Dal, the Americans and British got cold feet.

At the very last moment, they refused to recognize King Gyanendra's enthronement. If the palace today doesn't like the way Washington insists it is coordinating policy with London and New Delhi, now you know why.

More recently, why did the U.S. government have to declare the Maoists a terrorist organization only when Dr. Baburam Bhattarai emerged for peace talks in 2003 and was expected to head an interim government?

Four years after his enthronement, King Gyanendra is still in the process of defining the monarchy. From his perspective, too, the options are open.

What's the first thing a new king does? Plan his coronation. Have we seen or heard even faint hints of possible propitious hours?